The Daniel Morgan Monument at the corner of West Main and Magnolia streets in Spartanburg, South Carolina was erected in 1881 to commemorate the centennial of the victory at the Revolutionary War Battle of Cowpens. The statue was designed by John Quincy Adams Ward, and the columnar granite shaft on an octagonal base was designed by Charleston architect Edward Brickell White. The monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. Daniel McDonald Johnson shot photos of the statue in 2013 and 2016.

Battlefield oratory

Daniel Morgan’s leadership skills at the Battle of Cowpens resemble King Henry V’s leadership skills at the Battle of Agincourt as dramatized by Shakespeare. Each leader visited with his men around their campfires on the eve of battle and each leader gave a battlefield oration. Morgan’s promise that when the men returned home “the old folks will bless you for your gallant conduct” distantly echoes Henry’s claim that men back home would “hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks that fought with us.”

I’m not suggesting that Morgan modeled his oratory on Shakespeare; Morgan’s background as a semi-literate frontier laborer means that Morgan probably was not even aware of Shakespeare. I suppose that the eye-witness—Thomas Young—who recalled Morgan’s campfire conversations could have embellished them or even created them from his imagination. My theory, however, is that Morgan possessed the qualities of a great battlefield leader, and Shakespeare recognized the qualities of a great battlefield leader. Rather than Morgan imitating Shakespeare, I would argue that Shakespeare presented a timeless archetype that Morgan embodied.

Experienced leadership

Daniel Morgan knew how to lead men in battle. In 1777 George Washington sent Morgan to assist General Gates in the Northern Department. Morgan played a major role in the American victory at Saratoga, a turning point in the American Revolution.

The Sergeant William Jasper Monument in Madison Square in Savannah Georgia, was unveiled in 1888. It memorializes the Georgia Revolutionary War hero killed at the Siege of Savannah in October 1779 while attempting to rescue the colors of his regiment. Designed by Alexander Doyle of New York, the 5 1/2 foot bronze statue of Jasper portrays him holding the flag of the Second Regiment of South Carolina Continentals during the assault. He holds a sabre in his right hand, his hand pressed against the wound in his side. His bullet-ridden hat lies at his feet. Daniel McDonald Johnson shot this photo in 2011.

The war moves south

By 1780, the South became the focus of the war. The British captured Savannah and Charleston, and set up a chain of posts at Augusta, Ninety Six, Camden and Cheraw.

Washington sent his best military leaders to the South, He appointed Nathanael Greene to lead the Southern army and persuaded Morgan to come out of retirement.

Greene sent Morgan with a detachment to threaten the post at Ninety Six.

The British countered by sending a detachment under Banastre Tarleton to seek and destroy Morgan’s force.

Strategy

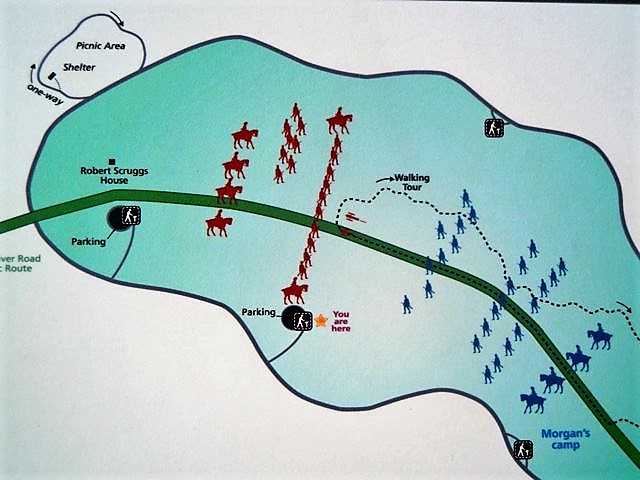

Morgan’s first stroke of tactical brilliance was choosing the field of battle.

He encamped at the Cowpens, a place where cattle drovers gathered in preparation for driving a herd from the backcountry to the markets in more settled territory.

Everyone in the backcountry knew how to get to the Cowpens, and as Morgan awaited battle more and more militiamen came in from the countryside.

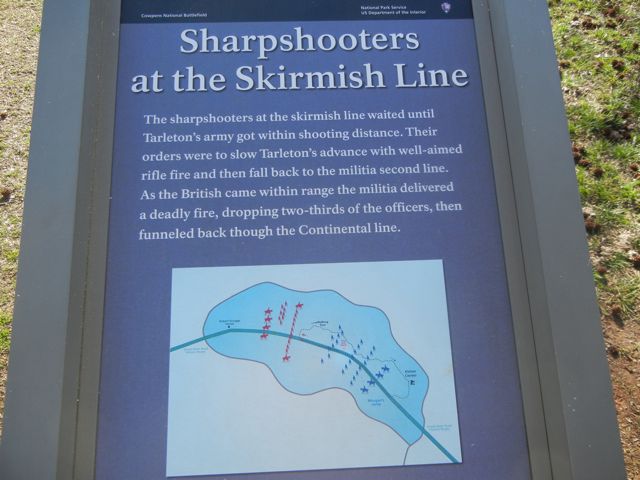

Morgan conceived a new way of using militiamen in battle, maximizing their strengths and minimizing their weaknesses. Their greatest weakness was their refusal to stand and fight against the bayonets of advancing infantry. Their most valuable strength was their accuracy in shooting a rifle. Morgan placed the best sharpshooters in the front lines.

He gave the sharpshooters permission to run for cover behind the patriot lines after they had fired a well-aimed shot.

Morgan placed militia units in the second line. He instructed the militiamen to fire two well-aimed volleys with their rifles or muskets. After that, they would withdraw in good order to safety behind the Continental infantry.

The Continental soldiers in the third line had hard-earned experience in conventional warfare, and Morgan knew he could depend on them to stand and fight against the British infantry.

As a reserve force, Morgan placed cavalry behind a low ridge.

Morgan explained his plan to his troops in person. He fit right in with the militiamen; being a backwoodsman and former wagoner, he talked like them and acted like them, and they considered him to be one of them. Historian M.F. Treacy described Morgan as “the very figure of the culture hero, bellowing in his teamster’s voice, laughing his deep-chested guffaw.” (Prelude to Yorktown, page 97).

Morgan had been recovering from malaria when Greene sent him out in rainy midwinter weather. His chronic sciatica flared up again. Riding a horse caused intense pain, even at a walk. As he visited with the soldiers at the Cowpens, he wanted to show them the scars on his back, but his rheumatism kept him from raising his shirt and he had to ask someone to raise it for him.

During the long, cold January night at Cowpens, Morgan moved through the camp, explaining his battle plan. Thomas Young—who was among the troops at the time—described Morgan’s conversations with his men:

… It was upon this occasion I was more perfectly convinced of General Morgan’s qualifications to command militia than I had ever before been. He went among the volunteers, helped them fix their swords, joked with them about their sweet-hearts, told them to keep in good spirits, and the day would be ours. And long after I had laid down, he was going about among the soldiers encouraging them, and telling them that the old Wagoner would crack his whip over Ben (Tarleton) in the morning, as sure as they lived. “Just hold up your heads, boys, three fires,” he would say, “and you are free, and then when you return to your homes, how the old folks will bless you, and the girls kiss you, for your gallant conduct!” I don’t believe he slept a wink that night! (Voices of the American Revolution, edited by Ed Southern, pages 181-182).

On the morning of January 17, 1781, scouts alerted Morgan that Tarleton was on the way. Knowing that the British had a long march ahead of them, Morgan let his men sleep awhile longer while he pondered and prayed.

At about an hour before sunrise, Morgan bellowed, “Boys, get up! Benny is coming.” (Treacy, Prelude to Yorktown, 97). Morgan knew that Tarleton was still five miles away and there was time for the men to eat breakfast.

Oratory

As the night drew to an end at Cowpens, the Americans took their battle stations before sunrise. Morgan shored up their resolve by going to their positions and speaking to them. Historian Don Higginbotham gives this description:

To the skirmishers in front, he said, “Let me see which are most entitled to the credit of brave men, the boys of Carolina or those of Georgia.”

Moving to Pickens’s militia, he delivered a fiery speech, pounding his fist into his palm as he spoke. He expected to see their usual zeal and courage, and he reminded them not to withdraw until they had fired twice at close range.

His words to Howard’s line were equally impassioned: “My friends in arms, my dear boys, I request you to remember Saratoga, Monmouth, Brandywine, and this day you must play your parts for your honor & liberty’s cause.”

Battlefield oratory was not uncommon in the eighteenth century, but it was seldom more effectively employed. Morgan struck a spark in his men. The often unpredictable militiamen were, as one American officer wrote, “all in good spirits and very willing to fight.” (Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman, 136).

The Battle of Cowpens

The British arrived at the Cowpens around sunrise. As Morgan had predicted, Tarleton, immediately launched an attack. British dragoons drew their sabers and charged the sharpshooters positioned in Morgan’s first line. The riflemen aimed and fired, and fifteen dragoons fell from their horses; the survivors galloped back to the cover of the British infantry.

Tarleton ordered the main body of his infantry to advance. The British infantrymen yelled as they charged, prompting Morgan to tell his men, “They give us the British halloo, boys, give them the Indian whoop.” (Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan, 137)

When the British came within range, the militiamen with Pickens fired a volley. The advancing infantry slowed down but kept coming. The militia fired a second aimed volley, and withdrew as instructed by Morgan.

Tarleton thought the militia had broken. He ordered fifty cavalrymen to pursue what he thought were panic-stricken men in flight. William Washington’s horsemen drove Tarleton’s cavalry away, and covered the withdrawal of the militia. Pickens and other officers tried to convince the militia units to regroup and reload.

Then Morgan rode up, sword in hand, and shouted, “Form, form, my brave fellows!” (John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse, 323).

The British infantry continued to advance, but because it had lost so many officers it did not stay in formation.

The line of Continental infantry Morgan had placed near the crest of a ridge fired a volley that stopped the British in their tracks. The disciplined, veteran foes exchanged fire at point-blank range.

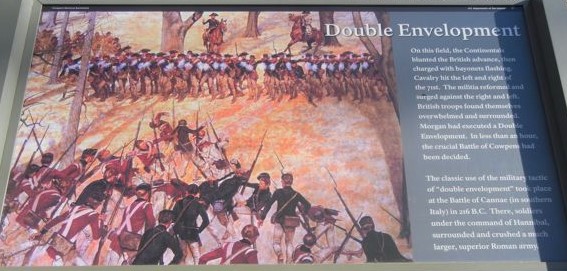

Tarleton then called on the 1st Battalion of the 71st Highlanders to execute a flanking movement against Morgan’s right. The battalion’s bagpipers played a traditional march as the Highlanders entered the fray. The Highlanders fired a volley that created confusion among the Virginians on the right. The battalion then charged in traditional Highland fashion, expecting to take advantage of the confusion.

Officers ordered the Virginians to maneuver into position to oppose the flanking movement. In the confusion created by the Highlanders, some of Morgan’s men misunderstood the maneuver, and soon the whole line was moving in order away from the British attackers.

The British assumed that Morgan’s entire army was in retreat, and gave chase. Because they were charging at a run through a stand of trees, the usually well-disciplined British troops disintegrated into a mob as they pursued their foes. The Highlanders closed to within ten to thirty yards before the Americans turned to fight some more.

Morgan’s men remained in formation as they marched toward the rear. Morgan picked a place to make a stand, and ordered them to halt. “Face about, boys!” Morgan told them. “Give them one good fire, and the day is ours!” (Buchanan, Road to Guilford Courthouse, 324). The Americans fired point-blank at their pursuers. Bodies of the killed and wounded covered the battlefield.

The Highlanders kept fighting hand-to-hand. Continental infantry charged the Highlanders with bayonets while Washington’s horsemen attacked the Highlanders from their left flank and rear.

The American militia charged the Highlanders’ right flank. The Highlanders began to retreat; many of them ran for their lives. Surrounded and without hope of relief, the Highlanders surrendered.

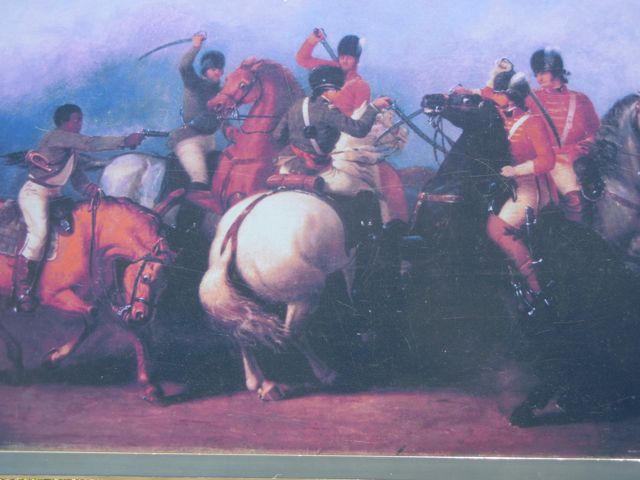

Tarleton, watching his infantry surrender and most of his dragoons flee, rallied fifty loyal horsemen and led one last desperate charge. The American cavalry met the charge and drove off the British dragoons.

Cavalry commander William Washington then took off in pursuit of Tarleton. Washington was alone ahead of his men when Tarleton and a few of his horsemen turned to fight. In hand-to-hand combat with a British dragoon, Washington broke his saber at the hilt. Washington’s fourteen-year-old black servant raced to his rescue and shot the dragoon in the sword arm.

Another British officer attacked Washington, but an American sergeant arrived in the nick of time and deflected the officer’s sword.

Tarleton himself charged in and swung his saber at Washington, who blocked it with his broken saber.

When Tarleton fired his pistol, he missed Washington and wounded Washington’s horse. Tarleton galloped away.

The Battle of Cowpens started at sunrise and was over within an hour. British casualties were about 110 killed, 200 wounded, and 500 taken prisoner.

About a dozen Americans were killed in the fighting at the Cowpens. Reports of the number of Americans wounded range from sixty to more than one hundred.

Morgan did not take time to savor his victory, because he knew the main British army under Cornwallis was a greater threat to his much smaller force than Tarleton’s detachment had been. By noon, Morgan moved out, and by nightfall his division had crossed to the north side of the Broad River. Before dawn the next morning, the division continued its rapid retreat and marched until sundown. Morgan detached a force to take the prisoners into Virginia, and led the rest of his division across the Catawba River. He had covered a hundred miles and crossed two rivers in six days.

Once encamped on the Catawba, Morgan stayed in bed in his tent, suffering from sciatica and a high fever.

Shakespeare’s Henry V

Morgan’s comradery with his troops on the night before battle resembles the prologue to Act IV of Henry V by William Shakespeare:

Behold

The royal captain of this ruin’d band

Walking from watch to watch, from tent to tent,

For forth he goes and visits all his host.

Bids them good morrow with a modest smile

And calls them brothers, friends and countrymen.

That every wretch, pining and pale before,

Beholding him, plucks comfort from his looks:

Thawing cold fear, that mean and gentle all,

Behold, as may unworthiness define,

A little touch of Harry in the night.

Morgan’s speech to “my friends in arms, my dear boys,” resembles Henry’s speech to “we band of brothers” in Act 4, Scene 3.

(Westmorland says)

O that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England

That do no work to-day!

(King Henry V says)

What’s he that wishes so?

My cousin, Westmorland? No, my fair cousin;

If we are mark’d to die, we are enough

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour.

God’s will! I pray thee, wish not one man more.

No, faith, my coz, wish not a man from England.

God’s peace! I would not lose so great an honour

As one man more methinks would share from me

For the best hope I have. O, do not wish one more!

Rather proclaim it, Westmorland, through my host,

That he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse;

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is call’d the feast of Crispian.

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when this day is nam’d,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall see this day, and live old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say “To-morrow is Saint Crispian.”

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words—

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester–

Be in their flowing cups freshly rememb’red.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd–

We few, we happy few,

we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day!!!